I’d always been a turtle behind the wheel, slow and steady. Didn’t get a driver’s license until I was twenty-four and had totaled two cars by the age of forty-eight, uncertain of where I was in space. Routinely drove off steep curbs. Somehow missed the dip that signified a driveway entrance or exit. Could never tell how far my own car was from the one just ahead. On mountainous roads I’d ask someone else to take the wheel, lie down on the back seat or crouch on the floorboards. Edges terrified me. I rode the brake, gulped fear, heart pounding. Never looked out the window with pleasure, even on planes. Didn’t care about seeing a carpet of clouds. I slid the porthole cover shut as soon as I sat down. Turned the overhead reading light on and zoned out.

Distance. Heights. Crowds. I couldn’t deal with everyday space and time. Hollowed out just looking at a clock. Immediately convinced I was late, I’d grab my purse, eyeglasses and keys, and head for the door. I was the woman who always showed up too early and waited out front in her car, the woman who claimed a seat closest to the plane gate two hours ahead of the flight.

Transitions were hard.

“Read the letters on the chart for me, please.”

They looked like Celtic runes or the Cherokee syllabary. E was easy, the top letter on the chart and one I knew well. E was the initial of my son’s first and last names. Also, the first initial of my adopted last name, and the official surname on my birth certificate, not the name I was born with but the name of my stepdad. S -- my initial from Real Dad -- was long gone.

“Were you ever hit in the head?” my ophthalmologist asked.

Fingernails in my arms hang on, hang on. Head bounced against the wall. Run. Run. Run, you little idiot. Get out of here. Slip out the door and out of the way. Move. Two years old on my trike, twenty blocks gone.

I’m leaving. I’m leaving. I’m out of here.

Not enough to go around. Not welcome, not wanted, no room for any of us.

Born to a woman who had to parcel out love to her nine children.

1. Me

2. Moody Sister

3. Baby Brother

4. Tomboy Twin

5. Platinum Twin

6. Baby Sister

7. Lawyer’s Son

8. Last Girl

9. Last Boy

Only the twins had the same father: a man my Stepdad tried to kill one night with a bottle opener.

Tore him apart and set Mama rambling.

After that night, she never lived in the same place for more than a year or so. She took off to avoid questions she didn’t want to answer from people paid to ask those kinds of questions: social workers, doctors, school counselors and law enforcement officers.

Mama distrusted authority and instilled that distrust in all her children.

Mile-high moxie, ruthless disregard of authority, and freedom of a kind I’d left behind, left behind and sometimes longed for.

Afraid. And still ashamed of my fear and my weakness, ashamed I wasn’t strong enough to carry my siblings away with me when I left. Afraid of being run over, demolished, and obliterated by the hate and disregard that had lived in Mama and lived on in them. That didn’t die with Mama. That seemed to never die.

“Here’s the thing,” the doctor said. “There isn’t a prism insert big enough to correct this. I’m going to have to send you to a strabismus expert.”

Strabismus? As soon as I got home, I looked up the term.

Strabismus, sometimes described as: crossed eyes, walleyed, lazy eye, wandering eye, or deviating eyes, was an imbalance in the muscles responsible for the positioning of the eyes, preventing the eyes from tracking together in a coordinated way.

Psychological difficulties included: social inhibitions, anxiety, and often, emotional disorders from the loss of normal eye contact with others.

Traitor was what my half-sisters called me, and worse.

When the twins were three, Mama had Baby Girl, the parting gift of some stranger in the night, and I knew that once again I would have to love her as my own. And I did. I loved her so hard and so strong; she called me mommy. She toddled toward me, arms wide open and trusting.

I held on to her the way I needed someone to hold on to me.

And then Mama had another baby, this time a boy. The kind she hated, the kind she never even tried to like. Born seventh in line, with a full head of black hair and dark inquisitive eyes. Eyes that took it all in from the get-go. I could tell. And I couldn’t take it. I had to get out of there, couldn’t try to love one more loveless baby one more time. The last I saw him he was fourteen months old, standing in his crib, watching and silent. And I was off to live with Real Dad and his new family.

Broken family, wrecked finances, for years involved with men who didn’t want me, harsh judgmental pricks, not tender or kind at all. The people in my life fluctuating, most were more acquaintances than friends, not as important as the ones I had left behind -- never as important as the kids in the car.

In many ways I was still in that car.

Cramped legs, clenched fists, and squinting eyes.

Stubborn. And driven. For as much as I moved forward, I also stood still. Afraid of what would resurface, I kept my life fragmented: these people here and those people there. Friends never met family. Family never met friends. I’d lived my life on the edge of every family system: biological, adopted, step, foster and married in.

Compartmentalized.

The only way I could deal. The only way I could keep it together. Then I fell in love with R, the first letter of relief, and the initial of my current last name, surname of the man I kissed under a round light in the sky. Greg. “What’s that enormous light in the sky?” I’d asked him that first night, because I’d never seen the moon so high, the world so bright.

And hopeful.

In the first photo taken of me with my second husband and his two children, I’m standing apart from them, arms crossed, head cocked to the right, squinting eyes aimed left. Body contorted. Inward. Hidden away. Protected.

The way you look at us, friends would say.

Lighten up. Don’t sit so far away. Don’t look like that.

See it this way.

Ten percent of the general population has strabismus; four percent of children have strabismus. Age of onset for naturally occurring strabismus: from two to three months to two to three years. The condition might be congenital, acquired, or pathological. As for a fix, the odds were not good. The chance of achieving stereoscopy in adult life was slight to none. I examined photographs from childhood. I studied my gaze in infancy, in early childhood, and found a level gaze at two and four. Sad eyes, yes, but eyes able to look directly into the camera, until age six and then not so much.

At six, I remember looking across the room at a favorite toy, a gyroscope. I remember seeing it split apart and become two. One gyroscope levitated, the other stayed on the bed. I was in awe. Transfixed by the magic I had made. I thought everyone looked so hard they made the objects in the world split and float apart.

The wonder didn’t last long.

By age eight, I avoided eye contact. Shied away from the camera. Looked down, to the side. Covered my face with a book. Adopted a stubborn stance of defense and resistance. Sat as close as I could to the TV and squeezed my eyes together. Pressed in on my temples as hard as I could. Struggled to bring the doubled images on the screen together in my head. Couldn’t see to catch softballs lobbed my way, failed to judge the distance between my bike’s fender and a friend’s and crashed. Stayed inside more and more with my moody sister. Upside down, we flopped backward into the canyon between our twin beds. Watched each other’s lips move, striking and odd and so comforting. I became obsessed with viewing the world that way. Wondered why all doorframes weren’t inverted, allowing you to step up and into a room instead of mindlessly gliding through portals.

“Look at the world and paint a picture,” my fourth-grade teacher said. “Make it look the way you see it.”

I chose the bloom of a blue iris, stuck in a water glass on her desk. Mushed the wet end of a watercolor brush into a cake of violet and transferred the flat world I saw onto the flat world of the paper with deceptive ease.

Transcribed the world of my own vision onto the world of the picture plane.

The code for depth already buried in the back of my brain, disconnected.

Unplugged.

To “put” something in perspective is to place it within a contiguous space, in sequence, with clear boundaries and borders, in context. Seamless.

Art blows that map apart. Has to.

Life never stays the same, in sequence with clear boundaries and borders.

In my twenties I made a special trip to The Museum of Modern Art in New York City to see Picasso’s Guernica before it was returned to Spain. Sat on the floor in front of that monotone mural and took it all in, transfixed by the light and the lack, by my recognition of the fractured world depicted: horrific conflict, child in the center, torch lighting the way. Cubistic. Drawn as much from what the artist knew to be true as what he saw in the world.

All art an abstraction, all vision an interpretation. The brain was an organ of interpretation.

“They’re not finished,” observers would say about my drawings and paintings, even my writing. “Why don’t you ever finish them? We want more!”

“They are finished,” I would answer.

So sure, I knew what I was leaving out. So sure, composition was a choice I made, that what I left out was purposeful.

Drawing was my skill, my knowledge, and my way to get attention.

Life was so hard.

I made the meaning I could.

Adapted.

I was so adept at adapting; I was eleven years old before someone in my life noticed something off with my vision. Grandma Iola, my paternal grandmother, watched me struggle to see the TV and took me to an eye doctor. After the examination, she let me pick out a pair of cat-eyed frames, along with a silver chain to hang them around my neck. So, I would never lose them. There’s one photograph of me wearing those eyeglasses, a black and white Kodak of a solitary girl standing on a gravel driveway in front of an old Chevrolet. A nerd girl in peg leg jeans, a button-down white Oxford shirt, and a corduroy jacket lined with fake shearling. Suede loafers with white socks on her feet, hair in a ponytail, stray bangs hung over and into the brand-new eyeglasses on my solemn face.

I didn’t even make it into Mama’s house with those cat-eyed frames.

The instant Mama saw me, she ripped them off my face and threw them back into my grandmother’s car.

“Ugly four eyes. No kid of mine will ever wear glasses.”

Mama didn’t like doctors. She only took us kids to a doctor when we needed shots for school attendance. Doctors were nosy. Mama didn’t trust them. She hadn’t gone to them when she was a kid, and she didn’t want their questioning eyes on any of her children.

“Mercy,” Grandma Iola said.

Mercy was the word Grandma Iola used whenever she had cause to wonder. She said it in surprise or disbelief or whenever she needed time to think. I would hear her say that word whenever I was afraid. Petrified that day, I adopted my paternal grandmother’s invisible faith, hoisted myself up from the curb where I had fallen and followed Mama into the house.

The next time I wore eyeglasses, I was forty-two years old, working as a photo researcher in the Los Angeles Times editorial library, with so much eyestrain I could barely think. For hours a day I looked through magnifying loupes, searched through Lektriever files for the best negative frame, browsed through online databases for this or that image, eyes in a squint, head throbbing. Queasy and disoriented, prone to double vision when I was tired, unable to pull my lazy right eye into alignment, and make it cooperate with my overworked left.

A body holds a head to suit the senses. I held my head askew. Turned my face to the right and looked at the world cross ways, eyes aimed in the opposite direction. I trained myself to look at the world sideways. Shot the people around me side-eye like a perpetual doubter.

Torso twisted to support my misaligned vision.

Head rotated to reposition my wandering right eye.

Neck and shoulders torqued to the right to accommodate my head.

Right hip rotated.

Right leg followed and right foot splayed.

Spine curved.

The waiting room of the Jules Stein Eye Institute in Los Angeles was full of parents with young children. Most of the kids were under three. Some were still in strollers; many wore eye patches like little pirates. I wondered how they could test pre-verbal kids with an eye chart.

Strabismus, if not detected and treated early, contributes to loss or lack of development of central vision. Early diagnosis increases the chance for complete recovery.

In the examination room, I took a seat in the exam chair and laughed. Across the room, shadow boxes held a menagerie of stuffed animals.

Above that was the Snellon eye chart.

The nurse came in and gave me a preliminary exam.

Showed me a card of geometric designs: nine rounded squares, and within each of them, a set of four concentric circles. “Point to the three-dimensional circles in each set,” the nurse said. “The circles that seem to rise off the page.”

As usual, I simply guessed. I did not know.

The world was a flat road stretching into the distance, parallel lines seldom converging, with objects and people popping into my field of vision as if from nowhere.

Twenty percent of murders take place within families. Reactive and regressive people respond with violence to upsetting or provoking stimuli. I’d read all about the makeup of criminals; I couldn’t get enough of the subject. I’d searched myself body and soul for the marks of Cain: odd lines in the palm, strange spaces between toes, creases on the tongue, and ears too low on the head.

Eyes unfocused.

The nurse left but told me to wait; the doctor would be in soon.

While I waited, I checked my phone for messages. Took a photo of the room and posted it online.

I’m here. Right here in this place.

We are animals with forward facing eyes. Eyes which converge to see close up and diverge to see into the distance. Eyes, which scan the world as we move through it.

Stereo and peripheral vision helps us do that.

I didn’t have either.

I was stereo blind. Stereo is the Greek word for solid. Real. Objects seen in three dimensions look solid, in and of the world. Located in space.

From early on, Mama wasn’t real and solid to me. For as long as I could remember, Mama was split into two people in my mind’s eye: the loving Mama who I imagined had been taken away and the mean version left in her place.

Get a grip, we say. Meaning: hold it together.

Mama couldn’t keep it together.

Two of Mama’s six girls were already dead by the time Mama died. Two of her three sons left before they were grown, before they had reached the age of accountability.

I couldn’t keep it together either. I hadn’t seen my own son in forever. Not since that night he’d left at seventeen.

When the nurse came back, she was with a portly man in a white lab coat. Finger puppets were stuffed in both his pockets. He introduced himself and sat down on a stool to read my chart. Then he handed the chart to the nurse and swung the phoropter over my face, a whirl of lenses, knobs, and prisms.

“Look across the room,” the doctor said. “And tell me what you see.”

“A pink pig, a blue elephant and, I think, a raccoon.”

He smiled. “No. I mean the letters on the chart. Start at the top.”

I read as well as I could. He measured the distance my eyes roamed as I moved them from side to side, trying to recognize every letter, to prove to him and to myself that I was okay.

“You should’ve had this done a long time ago,” the doctor said, and told me what he planned to do.

Operate. Once, twice, maybe three times. Whatever it took to correct the misalignment of my eyes. It had to be done. The difference between my left eye view and my right eye view was too great for my brain to combine into one contiguous picture. So, my brain suppressed the information from my right eye and only used the information from my left eye.

I stared at the doctor’s toupee and tried to absorb what he was saying.

He was going to fix me. Put his hands inside my head. Cut the translucent white skin over the surface of my eyes. Roll my eyeballs in the bony cradle of their sockets. Find the faulty muscle and alter it. Clip the loose muscle and tighten it. Cut the too-tight muscles off the surface of my eyeballs and move them down a notch or two. Stitch it all back down and call it done for now.

Who knew if the operation would work or not? The code for depth was buried in the back of my brain, disconnected all these years.

Unplugged.

“That’s deep,” Grandma Iola would say.

Depth a measure of seriousness, of sadness, a measure of how far down into the space of our psyche we are willing to go, to integrate, to pick up the pieces and come out whole on the other side.

After the first operation, I was shattered. In. Pieces.

Eyes a kaleidoscope.

Brain cells and electrical circuitry were reactivated and scrambling to make sense.

The eye drops burned going in. “Look up. There,” Greg said. “At the fixture in the center of the ceiling.”

I focused on that light. Every morning trained my eyes upward. And focused. Took charge of my vision.

What we make of what we see is our story. What we are able to see is our truth.

At fifty-eight, forty years after aging out of foster care, I had to learn how to see again.

The monocular cues developed over decades to help me decipher the world were useless to me now. Now those cues were scrambled, and I had to live with the reality of my actual vision while I retrained my eyes to work together. I was betting that if my eyes were not misaligned at birth or in early infancy -- and I knew from photographs that they were not -- my optic box had all the information I needed, and it was not too late to regain stereo and peripheral vision.

But it would take a lot of work.

Every morning as soon as I opened her eyes, I looked at the light fixture in the center of the bedroom ceiling and pulled the two images of that light fixture back together into one solid object.

I was determined to awaken my visual cortex, remind it, coax it to reconnect to my realigned eyes. I was determined to see what I had never seen before. I wore a pirate patch on my left eye to coax my stray right eye back to center. I binge-watched Six Feet Under on my iPad, a shallow box of light placed six inches from my face. I focused on those tiny scenes and pulled their doubled images back together in my head. Forced everything to come together: my eyes, thoughts, words, and life.

I stopped driving on the freeways.

Clung to daily habits: walked the dog through the streets of our tree-lined neighborhood, sorted the mail, the pieces that fell through the slot in the door and the pieces I scrolled through on my iPhone inbox. Everything was fractured and flat: my sight, my mood, and the weather. Fractured and flat and sequential, it all rolled by day after day. Day after day I used the same silver spoon, ate the same cereal from the same yellow-green Bauer bowl, the same uncertainty gathering, and the same debilitating doubt.

My stepdaughter cooked me a meal of delicious pasta.

My stepson encouraged me. “Remember to rest,” he said. “Your optic box is working hard to remember. You will need to rest.”

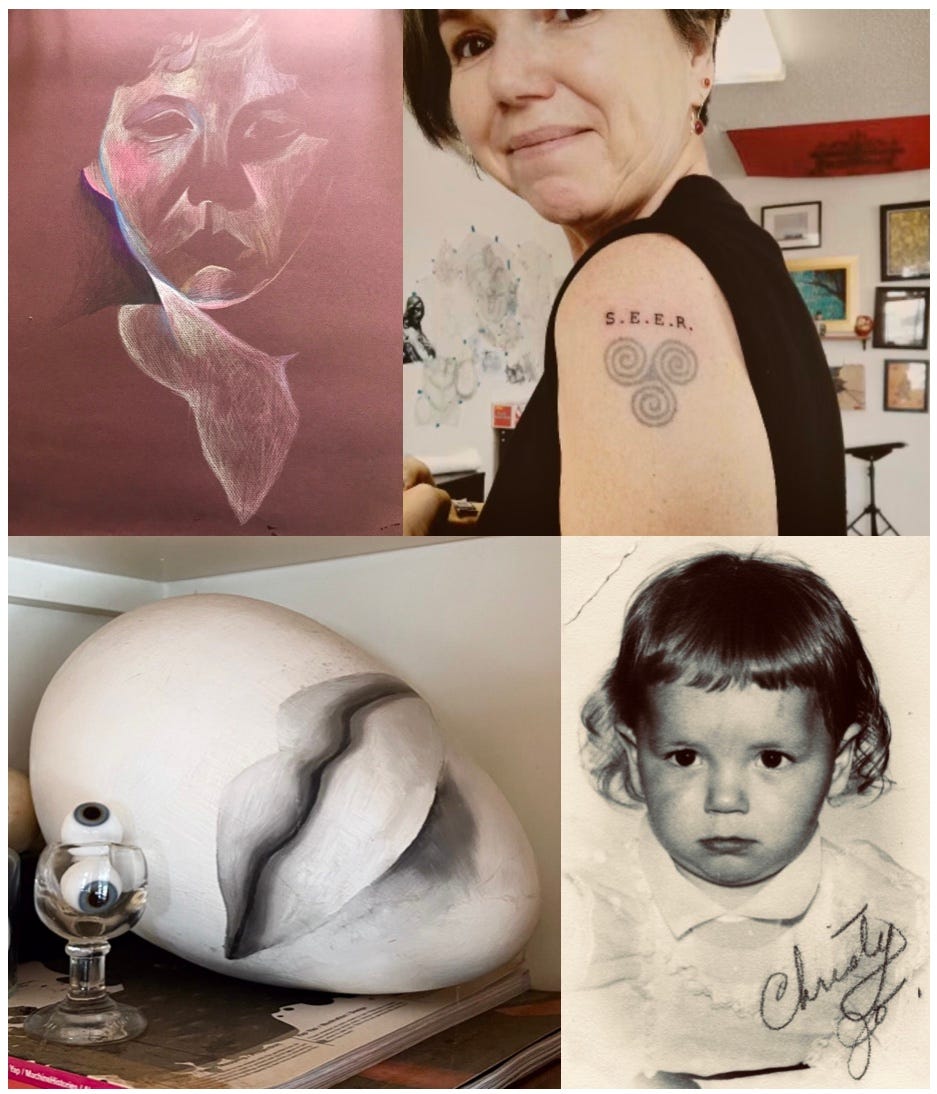

A year passed that way: tired and often dizzy, unsure of what I thought, felt, saw. Unable to correct badly placed commas, drive freeways or read for very long, I stared out the living room window watching birds land on a water bowl and promising myself that after this was over, I would get a tattoo on my left shoulder, my dominant side, my weakened side, the side of my body which had held my left eye steady while the right side twisted away in confusion.

Mama on the brain, in my head, in my flesh and blood and bones, in spirals of DNA, undetectable to the human eye, fractured bits of information and promise, of fate and possibility.

I promised myself I would get a tattoo on my left shoulder, my dominant side, my weakened side, the side of my body which had held my left eye steady while the right side twisted away in confusion. If I got through this, if I was able to bring it all together, I would get a tattoo. A tattoo of the first initial of all four of my last names.

We put the world together the only way we can, with our senses. We place what we know in context, and that context gives us a defined location in space.

What we are able to see is our truth, our reality.

Mama had two more babies after I left: number eight, another girl to ignore, and number nine, her last child, another boy to hate. Born when I was twenty years old, five years gone and at last in college.

I had never met either of them when I got the call Mama had died.

Mama’s story over and done, my story beginning.

A being captive, yet in my heart evolate, flying forth and away like the ancients, as if springing into being from an embryonic state. Like the ancients I was determined to defeat the cowardice in my own heart, the silence in my head, and the trouble in my life.

I, eye, aye, this is what I knew, what I could see, what I had seen, what I knew to be true. Some people will never love you. They will clobber you with their minds and hold you down.

Do not let them.

“Don’t stop painting,” E, my first husband said. “Whatever happens with us? This is your thing. This is what you need to do.” As if he knew.

It was uncomfortable to realize the role my faulty vision had played in my decision to leave my son in Oklahoma with his father when I left to go to art school in California. I wasn’t stupid. I saw the power I gave my ex by leaving. The moral high ground he ascended to when I left my son behind. Loaded up my Datsun and took off with my drunken boyfriend.

My identity as fractured as my vision; I erected walls around me. Hard walls. Flat walls. Walls I made and maintained. Walls consciously and unconsciously made to give me space, to give me time, time, and space to pull my vision together. Scarred with profound anxieties, I had already cordoned off my most painful experiences. I’d already accepted my fate.

In art school, the instructors pushed me to pick up a video camera. Put down the brush. Be like us or you can go home, hick girl. Pick up the tools of mass media. Use a video camera and deconstruct the dominant hierarchy. I tried. Put my right eye against the aperture and could not see. Went blind up against that machine. Literally could not see. Aesthetic production, they called it. Not art. Video flickers from expensive machines. A mechanical process meant to circumvent the body. Amend the body. Extend the body. MAGNIFY the body politic. They looked at my paintings of bodies, stacked and layered like history, like communal graves, like the back seat of a car, looked at my efforts and said: “Can you do without this obsession with the body? I mean. Does this say all you need to say?”

A year after the first surgery I had a second surgery.

As I was going under the anesthesia, the baby in the bed next to me cried and I allowed myself to be comforted by their mother’s voice. “Everything is okay. It’s okay. I am right here.”

Knocked out with those words in my head, I came back to consciousness propped up. The doctor was asking questions.

“Tell me which is sharpest? Clearest?” Click. Click. “Is it this one or that one?”

The doctor wanted to make sure my eyes were not over-or-under corrected. He wanted to make sure my eyes were coordinated, able to move together like the front wheels of a car.

Not misaligned, continuing to pull me off course.

On the way home, my husband stopped at a Peet’s Coffee to get us each a cup. I waited in the car while Greg went in. There were bandages over my eyes, the smell of disinfectant on my skin, stinging, and I was so curious. But I waited until we got home, until I got out of the car, to lift the bandages and open my eyes.

And bam! Binocular neurons fired and the world unfurled before me.

Distant hills curved into the sky. Every leaf on every Chinese elm, which grew in a row along our street, spiraled around me, one after the other. Plants grown out of the depths, rooted and round and three-dimensional.

I walked through the front door as if into a new world. A fifty-nine-year-old woman, forty- one years transitioned out of foster care, who saw, finally saw what she had to do to take her place in the story.

One day I danced in the living room to Janis Joplin.

Oh yeah, take it. Take another little piece of my heart now, baby.

No longer staring at the light in the middle of the ceiling, optic box busy unscrambling the chaos, pulling the doubled back together, no longer trapped in that space of powerless cowering, saying: I can’t, you can.

No longer an imposition, in the way and taking up more space than I should.

No longer adapting to the damage done, my center of gravity shifted.

My back swayed. My shoulders shimmied, my butt aligned, and my two feet followed.

The pain in my neck went away and new pains moved in.

If this had happened to me, what had happened to them, my siblings? The baby in the crib the day I left, the day I finally got away.

And my son, the child I was too afraid to love. The being I’d brought into this world and the being I was most responsible for.

I, eye, aye, a blind spot exists before the physical possibility of perception, a blind spot not darkness, but the absence of light. Fifteen degrees from the center of the retina, right where the optic nerve takes off for the rest of the brain. Right where the nerve leaves the retina for the brain. Right in that spot, there are no light-sensing cells. Right in that spot, there is darkness. No contrast, or illusion.

Empty.

And in that place of emptiness all the pieces come together.

S

E

E

R

Born Smith. Adopted Edwards. Married Embree. Married Rice. My true last name a combination, a hybrid mixture of all the surnames I’d taken on or had attached to my given name. Born Christy Jo. Called Christy. Then Chris. And finally, CJ. The entire world my blind spot, self in the dark center, unable to see until I could.

Like the terrapin in the old Cherokee tale, thrown into the stream by wolves: the terrapin dove deep under water into darkness and came up on the other side into light, escaping the wolves, alive but broken. His back fractured against a river rock, the terrapin sat on the opposite bank and sang I have sewed myself together. I have sewed myself together.

Gudayewu.

Goo-dah-yay-woo.

The pieces came together, but the scars remained.

A version of this essay was a runner-up in the 2017 Hunger Mountain Creative Nonfiction Prize and was published in that venue. When I wrote this essay in 2015 I was sixty-three years old and five years out from the experience described. Now at seventy I am posting the essay within the context of this newsletter about the aging out of a foster care and childhood trauma. Because we don’t know what we’ve lost until we’ve found it again.

Images left to right clockwise: 1. Christy Jo Smith as a toddler, soon to become Christy Edwards. 2. Egghead sculpture created by Chris Embree photographed alongside a cup of fake eyes. 3. Prisma color self-portrait, 1980 4. Chris J. Rice after getting the promised SEER tattoo.

Your writing cuts like a knife to the truth. I love it.

This one. So so powerful, beautiful. Made me cry.