Some people believe we are every being manifested in our dreams forever and ever, inhabiting every character’s part in every story in order to work out our life’s dilemma. Others believe that genetics ultimately determine who we are and who we can become. That free will is just a nice idea: you are your family, no matter how much you don’t want to be.

I still haven’t put any of those questions to rest.

Seventeen schools from kindergarten until high school graduation. No money for college. Debt death a million times over. Took me eight years to earn a college diploma. Still. I didn’t know what to be. An artist, a doctor, a director, an actress, a writer. A writer. From early on, scribbling in a notebook. Or in the air with an index finger. Mine is shorter than my ring finger. A vestige some say come from too much testosterone in the womb. Shared through the cord with a male twin who didn’t make it. I am that androgynous maker. Overly sensitive. And vulnerable. Revisiting and reworking the scene of the crime. Always about to break through, step out of the shadows and shine. Stand on the edge. Fully visible. At last. No longer covering my face with my hands. Gripped by debilitating self-doubt. For brief moments, hitting send on absolutely everything. And. Then. Once again held back. By self-doubt; ruinous and crushing.

Sometimes it takes a lifetime. When you have to play catch up just to stay even.

I aged out of the Missouri dependency system at eighteen and made a promise to myself: if the next eighteen years were as difficult as the first, I would leave this life for good.

My foster parents drove me to Oklahoma and dropped me off in the parking lot of Dorm A at Oklahoma Christian College, a conservative Bible school on the outskirts of Oklahoma City. A private Christian liberal arts college founded in 1950 by members of the Churches of Christ, the church my foster parents attended. Amazed I’d made it into college at all, I agreed to go there despite fears I would not fit in.

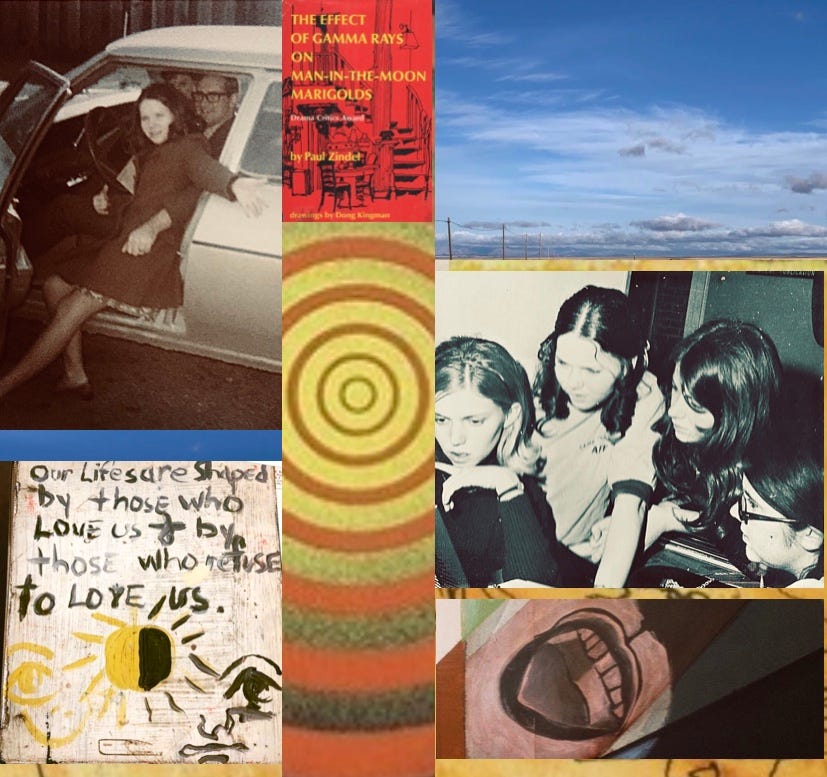

I kept my money in a metal Band-Aid box. Didn’t own or use a wallet. Carried loose change like a rattle in my patchwork purse, which shook when I walked, reminding me that I was not without bus money, a payphone quarter, or change to buy a bag of Doritos from a vending machine. I didn’t have much to unpack. Not even photographs of family to share with suite mates. Instead, I thumb tacked a poster to the dorm room wall.

Our lives are shaped by those who love us and by those who refuse to love us.

“Do you have siblings?” one suite mate asked.

“I have seven. Nine, if you count my real dad’s two girls. But I haven’t seen them in a long time. I don’t live with any of them.”

“Wow, don’t you miss them?”

My legs began the jitter dance, ready to run. There was so much I had trouble admitting even to myself. So many unanswerable questions.

Strong winds pushed against my body as I walked the path to class every morning. The wide sky pressed down on my head so hard, I couldn’t think. Afflicted and affected by all that I didn’t know.

My maternal grandmother, Clelus Annabelle Gipson had been born a few hours away in a town called Bunch. Her mother, my great grandmother, Martha J. Sixkiller, was born in 1885 in Stilwell, a city located in the sovereign territory of the Cherokee Nation. I had never met my great grandmother Martha and neither had Mama. Martha died young. Her family were “Old Settlers,” Cherokee who had voluntarily relocated, first to Arkansas and then to Stilwell, after the Removal. Driven from the rich land of Cherokee Nation, East, in what was now the state of Georgia and moved to where the earth was the color of dried blood.

I was their descendant, a pale girl with dancer legs, a shapely figure, a wide face, quick wit, dark sparkly eyes, a hearty and infectious laugh, and the ability to debate any issue. Any issue. Anything. A busy girl, a loud girl, and a sad girl, too. A girl who wrote bad poetry on the edge of all her school notebooks. Wrote in the margins and on the sly, in secret. Didn’t wear make-up and hardly ever washed her face. Scrubbed all over when she took a shower but couldn’t bear to look in a mirror for the time it would take to apply make-up. In the dorm bathroom, I scratched whatever body part itched and peered at my own reflection. Popped a few noticeable pimples, ran a brush through my shoulder length dark hair and left the dorm relieved to not have to think about what I looked like for the remainder of the day.

In the student union, I bought some fries and a Dr. Pepper and before I knew it, had told some random guy exactly how and why I’d become a foster child.

“Basically, I grew up in a car,” I said, sharing with a stranger what I wasn’t about to tell my suite mates. How for most of my childhood, we’d lived as strays, and drifters, lawless, homeless, and broke. A relief to say aloud for once some of what had happened to me.

“Most girls with childhoods like that either become prostitutes or they kill themselves,” the stranger said.

I smashed a French fry into my mouth, salty and hot, and made a silent promise to keep that shit to myself from now on. Stood up and ran all the way back to the dorm. Wanting to quit everything immediately: the work study job in the cafeteria dishing up black-eyed peas and creamed spinach to fellow students, the mandatory chapel services held every morning in the auditorium, hundreds of voices in prayer to our father who art in heaven, and the Bible classes with girls whose only ambition was to marry a missionary and travel the world preaching the gospel of Christ.

I needed guidance. But I didn’t know where to find it.

The next morning, I skipped chapel. Used the pay phone in the hallway off the dorm lobby to call my foster parents.

“I can’t do this.”

“Give it a semester,” my foster father advised. “Then, if you still don’t like it, you can quit.”

He didn’t say then you can come home. They’d recently moved from Carthage, Missouri, where I’d lived with them, to a farmhouse on a hill in McCune, Kansas. Their new house was a place for me to visit on breaks from school, not my home, and for sure not a refuge.

If I left school, I would be instantly homeless.

“Stick it out,” my foster father said.

People say they value you; they get you, even love you, but they don’t mean it. They just don’t want to hear about your pain. Mainly they don’t want to feel bad. Nobody wants to feel bad. They want a prettified version of your story. One they can live with.

I changed my work-study job from the cafeteria to the library.

Twenty hours a week, I shelved books, checked out books to fellow students, made Xerox copies for professors, and read everything I could get my hands on: psychology, history, poetry, and novels. I tested out of beginning English grammar and made extra cash writing term papers for all the religious kids who didn’t want to think about anything. I took theatre classes and art classes. I tried out for plays. I was in a hurry to make up for all the wasted time. Afternoons spent in motel rooms watching game shows and eating chicken out of a bucket. Years spent in the backseat of the Rambler reading Nancy Drew paperbacks, watching drive-in movies, eating drive through food. Body bent to fit the backseat of a car.

Not supported by anyone.

I wanted to be a good person, an honest person, but for a long time, I didn’t know what that meant. Good girls don’t get beaten up by their mothers and abandoned by their fathers.

Our father who art in heaven.

I stopped attending campus Sunday church services and hopped on a bus headed for West Main Mission, a Church of Christ outreach program on the south side of town. The preacher at West Main was said to be more social worker than Bible banger; neighborhood kids came to Sunday school classes for the silence and the comfort, for the free juice and cookies. I got that. I was a needy child, too, unable to sit still, and yet grateful for a safe and warm place.

I read the kids passages from “Good News for Modern Man,” while “Teach Your Children” by Crosby, Stills and Nash played on the record player. “Good News” was not as beautiful as the King James Version of the Bible with its ancient poetry. But the kids who came to the Mission didn’t seem to care. They were fine with whatever. Especially the little boys in Sunday School class, who were so wired on apple juice, cookies, and despair, they could barely sit in a chair or listen to a song all the way through. I held them in my lap when they would let me. Held on to them and they held on to me And for an hour every Sunday, everything was okay.

Helping others helped me to cope. My identity formed in the backseat of a car caring for my sisters and brothers. A carload of need I had tried so hard to fill.

Leaving them behind was burning a hole in my gut.

At West Main Mission, I became a Big Sister to a teenage girl a few years younger than me. When the girl ran away from home, I broke a door down to get her away from a drug dealer. Made a run at that flimsy door and kicked it in with years of pent-up rage.

“Come on,” I screamed. “Take my hand. Now! Take my hand and let’s get out of here.”

I got that girl out of danger and lost it. Struggled to breathe. That girl went home to her family, and I went back to school, to my studies. Shaking with memories I could not yet give words to. Back on campus, I didn’t go inside to my dorm room. I crossed Memorial Road, walked away from the college, and headed into the wild, into a section of undeveloped land separated from civilization by a blacktop road and a barbed wire fence. Got down in the dirt and belly crawled under the fence. Stood up and screamed with joy.

Rough-barked trees caught my clothing as I hiked into and through a field of cane breaks. Prickly vines scratched my arms and ankles as I made my own way through land dense with understory. Tangled with vines, briars, and scrub. I climbed a tall tree atop the hillside. Leaned against the gnarly bark and drowsy dreamed about my future. Listened to the wind in the treetops. The flutter and sway of branches overhead, dark tree limbs a drawing across a true-blue sky. Looked up into the cotton candy clouds and was liberated from the expectations of others, the curiosity of suite mates, the burden of society’s concerns. I was completely in the present, not the past, or the future.

Wild nature didn’t question my existence.

After class and every weekend, I walked into those woods, by myself but not alone. Quail scurried along the ground. Blue jays and cardinals flitted overhead. I didn’t know to look out for bobcat tracks or snakes underfoot. I carried snacks. Found a creek and sat down on the bank to nibble on grapes and saltine crackers. Tenacious scrub oak grew along the creek banks, the bedrock an anchorage for strong roots.

I hiked deeper into the underbrush, and found the ghost of a building, an abandoned cabin or house broken down, wooden and rotting into the earth. I climbed through a window and searched through the leftovers inside: moldy books, old newspapers, tarnished kitchen utensils, and brown glass medicine bottles half full of useless liquid. Looking through the debris in that ramshackle shed was like having a dream. Memories shifted in and out of chronological order. An episodic dissolve of time and place. Shutting the front door of my father’s house for the last time. Refusing to climb back into Mama’s car. Crashing through doors one more time.

Images dangled like lines of a poem.

I wanted to make art, but I didn’t know how or where to begin. I had never read my story between the covers of a book or seen what I knew to be true on the walls of a museum. Art and literature as an overcoming: not a love story, or a ghost story, but a lesson about time and trauma.

In art class, I drew the screaming mouth of a young girl, full lips, wide open and forceful, and saw my own transforming rage come alive on the page. Raw material applied to a flat surface, arrangements of shape and line and color—when I drew and wrote, I felt powerful. It was the only time I did. The only way I experienced the distance I felt from the world and the people in it as meaningful, almost beautiful, and useful.

Art became a place to hide, a way to disguise my deprivation.

One of my suite mates became editor of the yearbook. She asked another suite mate to write the copy, and she asked me to make a drawing for the cover.

I decided to do a line drawing of the campus as if seen from a bird’s-eye perspective. Put my drawing pad and pencils in a bag, slung that bag over my back, and climbed the fire escape ladder behind the Physical Education building. Climbed all the way up to the roof and walked around until I’d found the best vantage point. Sat down on the edge of the building, legs dangling, and began to draw the skyline. I was almost done when I heard a yell from below.

“You got to come down from there right now, young lady,” a campus police officer yelled up at me. Angry. “Who gave you permission to be up there?”

“No one.” My jaw tightened like a lid screwed down too hard.

“Well then,” he said. Baffled. “Come on down.”

Rules were everywhere, especially for the girls. Rules for where you could be and when you could be there.

One morning, I was given a demerit for walking barefoot.

“But why?” I asked the dorm’s resident chaperone. “What difference does it make if people go barefoot?”

“What would it look like,” the woman answered, “if we all went around with our shoes off?”

“A bunch of barefoot people?”

Brazen girl, they called me. A troublemaker, they said. Which didn’t bother me one bit.

All those years silent and watching, laying aside a book to look out the passenger side window into the gorgeous world, the light of the page and the light of the natural world whizzing by as one.

Shining a light on all that’s kept hidden.

I’d kept myself hidden, ready to run.

If you see me getting smaller, I am leaving became my life’s refrain, a Waylon Jennings song played on late night country and western radio stations. An old story condensed and set to music. I wanted to sing my own song, but I’d never learned to play an instrument.

Fall, spring, summer, then fall, spring summer again. I stayed in school semester after semester because I didn’t have anywhere else to be.

I took drama classes and tried out for school plays. I liked acting okay, but I liked the idea of directing better. Directing a play on a stage was an opportunity to bring all of my interests together: acting, reading, writing, interpreting words on a page, and visual art. I signed up for a directing class taught by the theater teacher, Dr. Alexander, and chose to put on a production of The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man in the Moon Marigolds, by Paul Zindel, a play I’d read over summer semester in a contemporary lit class taught by the Dean of the Humanities Department.

Instead of a printed program, I drew portraits of all the cast members and displayed them in the lobby of the school theatre. Friends in the theater school helped and friends who had never stepped on a stage helped, too. My friend Jim put the soundtrack together. My friend Patrick played the wheelchair-bound grandmother. My roommate Linda played Beatrice, the lethally short-tempered alcoholic mother, and my suite mates, Teri, and Maylan, played Ruthie and Tillie, Beatrice’s struggling daughters.

I was thrilled. And ambitious, too.

Only told people I wasn’t ambitious so as to appear lovable.

The day before opening night, I was called into the theater professor’s office. Dr. McBride, the Dean of Humanities was there with Dr. Alexander, and together they told me I had to make some changes to the script of the play.

Immediately.

“You will find the lines marked which need to be dropped,” Dr. McBride said, and handed me a censored script.

There were changes to dialog, action and set design, markups on every page.

“Can you promise us you will take care of this?” Dr. Alexander asked.

By then, I’d worked with him on five student productions. Had been a guest in his house for dinner. Babysat his son. I admired him. And now I wouldn’t be able to trust him ever again. Not if he was asking me to do this.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“What do you mean you don’t know?”

“I will ask the cast what they want to do. They’re the ones who’ll be out there in front of everybody. Not me.”

“Get back to us as soon as you can.”

At dress rehearsal that afternoon, I told the cast what the Dean and the theater professor had asked me to do and to a person, the cast said: No.

Opening night, I stood at the back of the auditorium and mouthed every word spoken. When my roommate, Linda, as the mother said, “God damn,” I silently nodded yes. When my friend Teri as shy Tillie prepared her experiment of marigolds exposed to radioactivity for her science fair, I applauded her resistance to her self-centered mother Beatrice. When my suite mate Maylan, as Tillie’s unstable sister Ruth, submitted to her mother’s will, bent to her mother’s efforts to stamp out any opportunity her daughters might have to succeed in life, I shivered with recognition. I stood in the dark at the back of the theatre applauding deformed yet beautiful flowers, and damaged sisters on divergent paths. So proud of our shared accomplishment and so curious where it might take me next. My beloved art teacher Annette and her kind husband Don were proud, too. After a celebratory dinner, we all had a slice of Annette’s famous strawberry rhubarb ice cream pie. I fell asleep on their couch and was awakened early the next morning by the ring of their wall phone.

I needed to get back to the campus ASAP. The Dean of Humanities wanted to speak with me.

“There were liquor bottles right out in the open on the stage,” Dr. McBride said.

“The mother character is an alcoholic,” I answered. I knew how alcoholic mothers behaved. I knew how to stage that mess. “I wanted the set to look believable.”

Linda and I had driven the country roads around campus pulling dozens of empties out of ditches.

“This is a Christian college,” the Dean replied.

“But how can you save people if they don’t even know what they’re being saved from?” I asked. Incredulous. I wasn’t being a smart mouth, I really wanted to know.

Besides, I didn’t believe every word the Bible said to be concrete and literal truth starting from the very first black and white page, woman made from man like a pot pulled off a spinning lump of clay.

I knew for sure I hadn’t been made in that way.

The Dean stood up. “You are not welcome back here next semester,” he said. “In fact, why are you still on campus? School is officially out.”

“I have laundry to do.”

“There are laundromats in town.”

Aged out and kicked out. Again. One more time kicked out with nowhere to go.

There would not be a place for me in my foster parents’ home. They were busy with a new baby and problems of their own. A week or so between semesters was one thing, but not this. I could visit, but not live with them. Most of my friends were going home to their parents fully supported and prepared to graduate in a year or two.

I left campus and didn’t return.

I lost the National Defense Student Loan, the Government Pell Grant, the work-study job in the library, the monthly allowance check sent from my former caseworker’s Missouri branch of American University Women, and for a time, I lost the emotional support of my foster parents.

I thought the struggle would be over when I left Mama’s brutal world.

But no, the staring eyes of normalcy, the curiosity and ignorance of people who hadn’t grown up like me, was almost worse than Mama’s cruelty.

This is a chapter from my still unpublished hybrid book, Driven: A True Fiction, A Family History, and A Memoir of Aging Out. It’s a hybrid work of fiction and nonfiction, a book which chronicles intergenerational trauma, female identity loss, and the alienation of disenfranchsied children. AKA a very American story. I am ccurrently unagented.

I'm waiting with baited breath for the next chapter. Your time in the woods and the library sound really important and life giving. I look forward to your posts every Tuesday.

Powerful writing. I love all your stories.